It happened late on a Monday night. After sleeping very soundly for an hour, I woke up and could not fall back asleep. It seemed to be my latest disordered sleep pattern. And, just like other nights when sleep eludes me, I was roaming the house. As is often the case, that night’s roaming found me in the kitchen, engaging in poor choices with a late-night ice cream snack. As I was standing at the sink, I gasped suddenly. It felt like my heart had been dropped into a very deep tunnel, and it was struggling to stay connected to my body. This struggle caused it to begin racing; I felt like I’d just run a 100-metre sprint, all while standing still. I headed to the couch, laid down, and tried to get my body under control, thinking if I fell asleep, I might feel better. I had a fairly strong inkling as to what was going on, as well as what I needed to do to resolve my racing heart, but for the moment, I wanted to stay put.

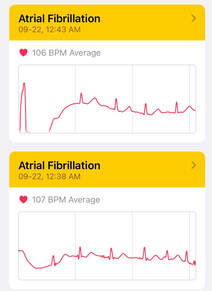

After 30 minutes or so, I gave up and went upstairs to try lying in bed. I ran into my teenage daughter in the hall, and filled her in on the situation. She suggested I check my heart rate on my Apple Watch. It was registering a heart rate of 110 beats per minute—normal resting heart rate is 60 to 80 beats per minute. As I suspected, my heart wasn’t working properly. It was around this time (duh!) that I remembered my watch also had an ECG (electrocardiogram) app. Thirty seconds later, and my husband, who had since woken up, was getting dressed. I was in atrial fibrillation (afib) and I needed to go to the hospital. I knew that’s what it was earlier, when I was standing in our darkened kitchen, but denial is not just a river in Egypt. By 12:15 am, my husband was dropping me off at our local hospital—COVID-19 restrictions meant it was a solo visit for me—and I promised to text him with updates. When it comes to heart issues, they don’t mess around, and I was in a bed in emergent care, hooked up to a heart-rate monitor in half an hour. Before I got dressed and headed home the next morning, I spent a total of seven hours with my heart racing, not being able to return to a normal rhythm. It would take some aggressive interventions to reset my heart, and I’ll tell you how that unfolded. First, though, let’s back up a bit and I’ll explain why I wasn’t surprised about the afib diagnosis. What is afib? Atrial fibrillation, or afib, is an irregular, chaotic heart beat, where the upper chambers of the heart—the atria—beat out of rhythm with the lower chambers—the ventricles. Left untreated, afib can lead to strokes, heart failure, and other heart-related complications. I know all about afib, because we have a family history of it, which increases your risk of developing afib by 40%. About four years ago, I had landed in the same hospital, with symptoms of a potential heart attack. Thankfully, it wasn’t, but the subsequent follow-up at the Ottawa Heart Institute discovered an atrial flutter, which is often a precursor to atrial fibrillation. The cardiologist indicated that, as long as a flutter resolved itself within a minute or two, there was no reason to seek medical attention. If it lasted longer, he advised me to go to the emergency department immediately. For the next four years, I only noticed my fluttering heart from time to time. Until I started noticing it every single day. It coincided, unsurprisingly, with the unfolding of the global pandemic now known as COVID-19. In addition to palpitations, shortness of breath, weakness, and fatigue, anxiety is a symptom of atrial flutter and fibrillation. I can unequivocally state that I am not the only person that was experiencing anxiety as a result of the spread of COVID and the ensuing lockdown measures. When lockdown began, doctors’ offices were closed. I thought about calling my doctor, after a month of shortness of breath, constant fluttering, and heightened anxiety, but I didn’t. Since the office was closed, the most I could hope for was an appointment over the phone. I knew they’d be unlikely to prescribe any medication in this situation—instead advising me to go to the hospital—but it didn’t feel urgent enough to use up vital health-care resources during a pandemic. I chalked up my symptoms to the current state of affairs, and figured my heart would sort itself out in due time. But it didn’t, and I now found myself lying in the hospital, heart racing, hooked up to multiple machines, awaiting my blood test results and a visit from the ER doctor. The treatment for afib involves cardioversion, wherein your irregular heart beat is converted to a regular rhythm, either with chemical or electric means. As you can imagine, the chemical—i.e., medication—option is the preferred first avenue, as it’s less harsh than delivering an electrical shock to your body. And that’s what the doctor suggested, though he did advise me that the medications only work for 50% of people. Two hours later, we had discovered that I wasn’t one of the lucky half who respond to the meds. So, the prep began for an electric cardioversion. Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve seen how COVID has changed everything, including hospital protocols. For a procedure like electric cardioversion, that meant transferring me to an enclosed room and waiting for all members of the medical team to don appropriate PPE (personal protective equipment). The first thing I felt when I woke up after the procedure was a normal heart beat. Although I was wiped out—from a night of no sleep in the hospital, an hours’-long racing heart, and the after-effects of being shocked—I was also relieved and happy that my ordeal would soon be over. The doctor explained to me that he didn’t feel I needed anticoagulants (to prevent a possible stroke), because I didn’t have any of the standard risk factors for afib. In the days following my hospital visit, I spent time researching atrial fibrillation and talking to my father, who shares the same diagnosis. Other than family history, the only other risk factors I had were stress and poor sleep. Well, I’ll be. Stress and poor sleep during a global pandemic. Again, I can say that, without a doubt, I wasn’t the only person experiencing stress and poor sleep. But I had to address it, if I was going to prevent a relapse and another hospital visit. The job was mine, and only mine. I’m working on it every day, putting myself first, and awaiting a follow-up appointment with a cardiologist. I feel better because I know I have the power to keep myself healthy, not to mention the motivation. And I’ve made a pact with myself to listen to my body and act on what it’s telling me. As women, we tend to put our needs behind others, often to the detriment of our health. We all need to take charge of our own health and well-being, here are some suggestions that I’m planning to implement in my own life. I hope this list will help you too. 1. Make the call. Don’t put your own health on the back burner. If something feels off, call your health-care provider and book an appointment. 2. Take charge of your body. Address the little things before they become big things. I knew at the beginning of lockdown that something wasn’t right with my heart, but I hoped it would go away on its own. 3. Track your symptoms. Telling a doctor you feel “off” doesn’t really help them help you. Be specific, descriptive, and methodical. If you can share with them a timeline of symptoms, they’ll have a better understanding of the severity and progression of your condition. 4. Be your own advocate. You know your body better than anyone else, so be firm if someone tells you, “it’s nothing, I’m sure.”

1 Comment

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

AuthorAmanda Sterczyk is an international author, Certified Personal Trainer (ACSM), an Exercise is Medicine Canada (EIMC) Fitness Professional, and a Certified Essentrics® Instructor. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed